Chapter 2

Experience of patients and access to treatment

2.1

As outlined in Chapter 1, the committee has received over 1000 personal

submissions from or on behalf of Australians suffering from chronic

debilitating symptoms. The committee is deeply concerned by evidence that many

submitters have experienced significant challenges in accessing appropriate

healthcare to address their symptoms. In particular the committee is concerned by

evidence that suggests submitters have been insulted and humiliated by some

medical practitioners when seeking treatment.

2.2

This chapter examines the experience of submitters in accessing

treatment, particularly those diagnosed with Lyme-like illness. It examines how

the ongoing debate about whether Lyme disease is endemic to Australia

contributes to the perceived stigma about diagnoses of Lyme-like illness and

impacts on the ability of patients to access treatment. It also examines the

treatments prescribed by Lyme-literate practitioners and allegations that these

practitioners are unfairly targeted for disciplinary action by medical

authorities.

Experience of sufferers of chronic debilitating symptoms

2.3

Submitters suffering chronic debilitating symptoms can be divided into four

main groups:

-

those who acquired and were diagnosed with classical Lyme disease

in an endemic area overseas;

-

those who acquired their illness overseas but weren't diagnosed;

-

those who became ill following a tick or other insect bite in

Australia; and

-

those who have experienced a long-term chronic illness in

Australia and may or may not have been bitten by a tick or other insect.

2.4

The common experiences of patients in these groups are summarised below.

Illness acquired overseas

2.5

A small number of submitters explained that they acquired their illness overseas.

In some cases, patients became ill following a tick bite in an area where

classical Lyme disease is endemic.[1]

In other cases, patients do not recall a tick bite, but became ill following

another kind of bite (such as bed-bugs).[2]

A number of submitters do not recall any kind of bite and their symptoms did

not manifest until after returning to Australia.[3]

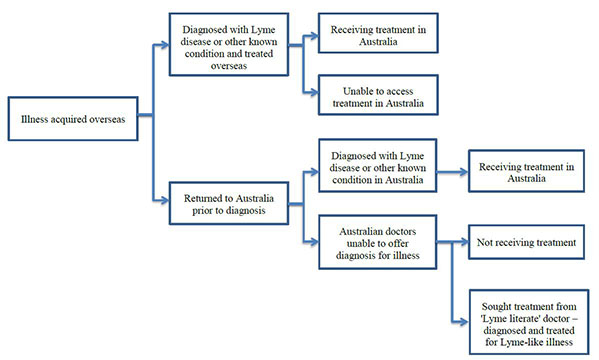

The common treatment pathways for these submitters are illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 – Patient treatment pathways –Illness acquired overseas

Illness acquired in Australia

2.6

The majority of submitters stated that they acquired their illness in

Australia. In many cases submitters had no history of travel to an endemic area

for classical Lyme disease.

Illness following tick bite

2.7

Some submitters state that they became ill immediately following a tick

bite in Australia. Symptoms described by these submitters include a rash around

the bite and a range of symptoms including fatigue, arthritis and chronic pain.[4]

2.8

In some cases, submitters were diagnosed with other known tick-borne

infections, such as Q fever, Spotted Fever, Rickettsia, Queensland Tick Typhus

or allergy to tick toxin, and received treatment.[5]

2.9

However, in most cases, the submitters state that medical practitioners

were not able to identify or diagnose the illness, or offer any effective treatment.[6]

Long-term chronic illness

2.10

The largest group of submitters is those who have experienced a

long-term chronic illness. In many cases, these submitters cannot recall being

bitten by a tick. In cases where submitters can recall a tick bite, this may

have predated the onset of their illness by a number of years.[7]

2.11

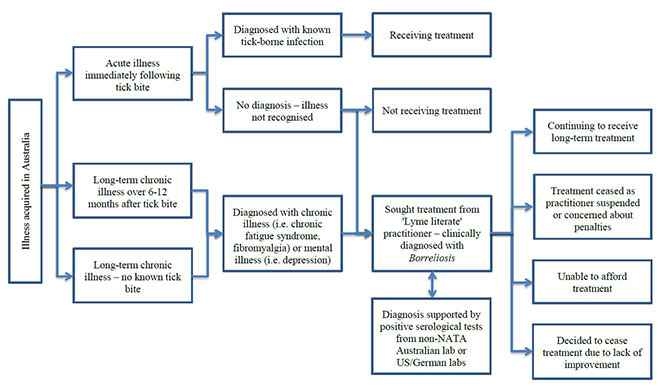

Figure 2.2 outlines the treatment pathways for these submitters.

Figure 2.2 – Patient treatment pathways from submissions – Illness acquired

in Australia

Treatment for patients

2.12

The committee heard that patients diagnosed with chronic debilitating

symptoms experience significant difficulties accessing diagnosis and treatment

from Australian healthcare services.

Illness acquired overseas

2.13

Submitters who acquired their illness overseas expressed particular

concern that Australian medical practitioners may not recognise or effectively

diagnose overseas illnesses, such as classical Lyme disease.

2.14

The committee heard that as part of the Chief Medical Officer's Clinical

Advisory Council on Lyme Disease, the department has been working with states

and territories to raise awareness and assist with the diagnosis of classical

Lyme disease through the development of the Australian guideline on the

diagnosis of overseas acquired Lyme disease/borreliosis. Dr Gary Lum from

the Department of Health (department) told the committee:

This guide was developed with the assistance of patient

advocates as well as experts in immunology, microbiology and infectious

diseases. The guideline was shared with Australian general practitioners,

emergency physicians, other relevant specialists as well as the Australian

Medical Association.[8]

2.15

However, evidence from some submitters with a history of travel to an

area where classical Lyme disease is endemic suggested that some Australian

doctors may not be aware of Lyme disease and the appropriate methods for

diagnosis and treatment. For example, one submitter noted that he acquired Lyme

disease in the United States (US) following a tick bite and was diagnosed and

treated by US doctors. Upon returning to Australia, he continued to experience

symptoms but struggled to get appropriate treatment:

For me the issue was not so much that the disease was active,

it was that doctors were unable to understand the left over side effects that

continue to deteriorate my general health and well-being ... I would love to see

more education and awareness about Lymes disease here in Australia,

particularly around managing the ongoing side-effects.[9]

2.16

Similarly, another submitter who was bitten by a tick in the US

expressed frustration at not being treated for Lyme disease in Australia:

People say being diagnosed with cancer is very scary, but try

being diagnosed with a potentially fatal disease when there is no help from the

medical profession nor support from the Government.

Regardless if the Lyme bacteria is in Australia or not, I was

bitten in the USA, so why shouldn’t I be treated? People who contact Malaria or

tuberculosis overseas can receive treatment in Australia.[10]

2.17

Dr Lum told the committee that despite efforts by the department to

educate practitioners, there was a risk that people infected with classical

Lyme disease overseas may not be appropriately treated in Australia:

We recognise that people infected overseas who return to

Australia have a risk that their classical Lyme disease will not be recognised

or appropriately treated, in spite of our regular advice to Australia's doctors

to pay attention to this situation.[11]

2.18

Dr Lum noted that the department was committed to education and

awareness raising of classical Lyme disease, but acknowledged it could do more

to communicate with the medical profession:

What the department has been trying to do is communicate with

the medical profession. If, as part of the Senate inquiry and as part of the

recommendation, we could possibly do more to communicate with the medical

profession on this, we certainly would.[12]

Illness acquired in Australia

2.19

More commonly, submitters have acquired their illness in Australia, but have

not been able to be readily diagnosed and treated by Australian medical

practitioners.

2.20

As discussed in Chapter 1, many of these submitters have been diagnosed

with Lyme disease or Lyme-like illness by 'Lyme literate' practitioners.

However, due to the significant debate in Australia about the existence of Lyme

disease, these submitters noted that they have experienced significant

challenges in accessing treatment in Australia.

The Lyme disease debate in

Australia

2.21

The existence of Lyme disease in Australia is highly controversial and

has attracted significant media attention and public debate. This debate

relates to two closely related questions:

-

whether the causative agent for classical Lyme disease (either

known Borrelia species such as B. burgdorferi or an as yet

unidentified Borrelia species) is endemic to Australia (i.e. has been

identified in Australia); and

-

consistent with the international debate about 'chronic' Lyme

disease, whether the chronic debilitating symptoms experienced by Australian

patients are caused by an ongoing active infection of Borrelia and

associated co-infections, or another as yet unidentified underlying cause or

causes.

Is classical Lyme disease endemic

to Australia?

2.22

The position of Australian Commonwealth, state and territory governments

and medical authorities is that the causative agent for classical Lyme disease

is not endemic to Australia.[13]

In their submissions to the inquiry, these authorities state that there is no

evidence to suggest that B. burgdorferi or any other Borrelia

species known to cause Lyme disease have been identified in Australian ticks or

patients.[14]

In his 2014 progress report on Lyme disease in Australia, the Chief Medical

Officer (CMO), Professor Chris Baggoley, stated that there is no evidence that

the bacteria causing Lyme disease are endemic to Australia:

There is still no routine finding of Borrelia spp in

ticks in Australia.

The conclusive finding of a bacterium that could cause Lyme

disease-like syndrome in Australia has yet to be made. Such a finding would put

beyond doubt the existence of Lyme disease, or a Lyme disease-like syndrome in

Australia.[15]

2.23

Most submissions from medical authorities[16]

support the Royal College of Pathologists Australasia (RCPA) position paper on

diagnostic testing for Lyme disease in Australia that states that:

Only a genuine case in a non-travelling Australian patient

would confirm the disease as being present in Australia.[17]

2.24

The CMO has stated that other 'vectors and routes of transmission are

postulated, but yet to be demonstrated'.[18]

In evidence to the committee, Dr Gary Lum noted that there may be a range of

possible causes for Lyme-like illness:

In the context of evolving Australian research data, we need

to consider that the cause may not be limited to a single bacterial species.

Parasitic and viral causes, as well as environmental toxins, should also be

considered for investigation, as well as other potential medical explanations.[19]

2.25

The first Australian cases of a syndrome consistent with Lyme

disease were reported in the Hunter Valley region of NSW in 1982. Further

clinical cases were reported on the NSW south and central coast in 1986, and in

Queensland between 1986 and 1989.[20]

Since these cases, there have been a number of studies examining whether

locally acquired Lyme disease exists in Australia. According to a recent paper

summarising research into Lyme disease in Australia, these studies have found

no conclusive evidence that indicates the presence of the causative agent for

Lyme Disease—Borrelia burgdorferi—in Australia and 'the diagnoses of [Australian] Lyme Borreliosis ... have

been primarily by clinical presentation and laboratory results of tentative

reliability and the true cause of these illnesses remains unknown'.[21]

2.26

However, patient advocacy groups and some medical practitioners

challenge this position and state that Borrelia bacteria known to cause

Lyme disease are endemic to Australia. These groups argue that Lyme disease is

a 'hidden epidemic' in Australia. They are concerned that there have been a

number of cases reported in the media of Australians who have been diagnosed

with Lyme disease acquired in Australia, but that these patients have been

'ignored' by the Australian health care system.[22]

2.27

In its submission, the Lyme Disease Association of Australia (LDAA)

suggests that evidence over the past fifty years that has demonstrated the

existence of an endemic species of Borrelia known to cause Lyme disease in

Australia has been 'systematically ignored' by medical authorities:

The presence of Borrelia, the causative agent of Lyme

disease, was established in Australian fauna in 1959 and human cases of Lyme

disease have been reported since the early eighties. Australian authorities

ignore this evidence.[23]

2.28

These groups highlight recent studies by Dr Peter Mayne, a retired NSW

medical practitioner, that suggest infection from B. burgdorferi has

been acquired in Australia by one patient and can be transmitted by Australian

ticks.[24]

However, the Communicable Diseases Network Australia has highlighted that the

absence of a published method to facilitate the replication of this finding

undermines its significance.[25]

2.29

Other groups, such as the Karl McManus Foundation, a charity that raises

funding for tick-borne disease research at the University of Sydney, assert

that the causative agent in Australia is not the same as classical Lyme disease

overseas, but an indigenous, Australian species of Borrelia:

...we do not have Borrelia burgdorferi, or Lyme disease,

in Australia. What we have is a unique Borrelia infection.[26]

2.30

The diagnostic procedures for testing for Borrelia bacteria in

Australia are examined in detail in Chapter 3.

Is an ongoing infection of Borrelia

bacteria responsible for chronic debilitating symptoms in Australian patients?

2.31

As noted in Chapter 1, the committee has heard that Australian

governments and medical authorities do not agree that the chronic debilitating

symptoms described by Australian patients are caused by an ongoing Borrelia

infection. These authorities assert that there is no evidence that the Borrelia

bacteria that cause Lyme disease are endemic to Australia and suggest that

there may be another as yet unidentified underlying cause or causes.[27]

2.32

For example, Professor Stephen Graves from the RCPA told the committee

that there is 'clearly something in Australian ticks, or some species of

Australian ticks, that is making some Australians sick',[28]

but it is unlikely to be caused by Borrelia:

I actually do not think what we are talking about is the Borrelia

infection. It is not classic Lyme disease. It is not a Borrelia

infection, although I am keeping an open mind on that possibility—but I do not

think it is. What is it?[29]

2.33

Dr Margaret Hardy, a research fellow at the University of Queensland's

Institute for Molecular Bioscience, told the committee that due to Australia's

geographic isolation, unique species of ticks and host animals, it is unlikely

that a Borrelia species similar to the Borrelia bacteria found in

North America and Europe would also be found in Australia:

America and Europe are much more geographically close as

well, so it would make sense that if you had two co-evolving types of Borrelia

you would see them across that close geographic range rather than coming all

the way up from there, missing Africa and Asia entirely, and popping up over in

Australia.[30]

2.34

Whereas Australian medical authorities suggest that the cause of the

chronic debilitating symptoms described by patients is not yet known, patient

advocacy groups assert that the cause is infection with Borrelia, together

with a range of other bacterial co-infections.[31]

These groups highlight that chronic Borrelia infection is just one of many

co-infections that are transmitted to humans by ticks and responsible for

causing chronic debilitating illness. For example, the LDAA submitted:

Emerging international research shows that Lyme disease is

rarely ever found in isolation of other pathogens; our research supports that

... Typically these are referred to as co-infections, but they are individual

and sometimes life threatening infections in their own right. As well as Borrelia,

an infection from each of those pathogens increases the complexity in the type

of symptoms patients actually endure.[32]

Tick-borne illnesses in Australia

2.35

The committee heard that due to the debate about Lyme disease, some

medical practitioners have limited awareness of other possible tick-borne

illnesses. A number of submitters reported that on presenting to their GP with

tick bites they were not offered any specific treatments and were told that

there are no tick borne illnesses in Australia. For example, Ms Linda Ebden

told the committee in Perth about her consultation with her GP:

I was covered in tick bites. He said to me: 'You have an

allergy. Go home and take some Phenergan.' I said to him, 'Is it possible that

it is something from the ticks?' He said, 'No, we do not have tick bite

diseases in Australia.' So I never learnt to protect myself. I thought being

bitten by ticks was just part and parcel of living in the hills.[33]

2.36

Ms Natalie Young, a National Parks Officer in NSW, noted in her

submission that she experienced over 300 tick bites over the course of her

career. As a result she suffered a range of debilitating symptoms including

headaches, fever, migratory pains and anxiety. Ms Young noted:

Doctor after doctor refused to acknowledge my large number of

tick bites as a causation of my illness even though I had had over 300 tick

bites at work over seven years. Local GP's were at a loss to explain my

illness. After I saw approximately ten local GP's, the referral process started

to specialists of varying fields. GP's were considering diagnoses of Chronic

Fatigue Syndrome, Tennis Elbow, Lupus, post-viral infections to Barmah and Ross

River Fever but as my disease severity worsened, they ruled these out.[34]

2.37

Whereas the committee acknowledges that there is significant debate

about whether or not Borrelia bacteria known to cause Lyme disease are

endemic to Australia, evidence to the committee suggests that both patient

advocacy groups and some medical authorities agree that there are likely to be

other pathogens in Australian ticks making people sick. Professor Peter

Collignon told the committee:

Ticks can cause lots of diseases, not only in Australia but

overseas. I think there are probably lots of organisms in ticks—bacteria and

even viruses—that we do not know of yet, so I think we have to keep an open

mind about what diseases may be transmitted by ticks and what therapy is available

or should be used for them.[35]

2.38

According to the department, there are 70 species of hard and soft ticks

in Australia, of which 16 species of hard ticks have been reported to bite

humans. The Paralysis Tick (Ixodes holocyclus) is understood to be

responsible for 95 per cent of tick bites in Eastern Australia.[36]

In Western Australia, a completely different species of tick, the ornate

kangaroo tick (Amblyomma triguttatum), is responsible for most tick bites

in humans.[37]

2.39

Ticks are hosts and vectors of a number of parasites, bacteria and

viruses. The main organisms that may be transmitted by ticks and associated

with disease known in Australia are outlined below:

-

Anaplasma – causes disease in cattle (bovine anaplasmosis,

or 'bovine tick fever') and dogs (canine anaplasmosis);

-

Babesia – a significant cause of disease in cattle (Bovine

babesiosis) and dogs (Canine babesiosis);[38]

-

Bartonella – causes disease in domestic and wild animals

including cats and kangaroos – uncertain whether it can cause human disease;

-

Ehrlichia – causes disease in dogs worldwide but has not

been recognised in Australia;

-

Francisella – relatively rare and no evidence to suggest

pathogenic for humans;

-

Rickettsia – causes several diseases in humans including

Queensland tick typhus (Rickettsia australis), Flinders Island spotted

fever (Rickettsia honei), variation of spotted fever (R. marmionii)

and Q fever (Coxiella burnetii – rarely tick-borne).[39]

2.40

The incidence of these tick-borne illnesses and their effects on

humans are not clearly known. A number of groups, including the RCPA, suggest

that further research needs to be undertaken into these other tick-borne

diseases and their impacts on humans.

Professor Stephen Graves told the committee:

Let us say it is bacteria, for argument's sake. Which one is

it? Or is it more than one? We cannot tell because we do not have the assays to

detect those bacteria or the antibodies produced in response to those bacteria

in the patients, because those assays have not been developed. That research

has not been done, and that is because the money has not been made available to

do it. Sorry to come back to money, but that is really what it takes ...

Someone has to look at Babesia and other protozoa that might be

responsible, and somebody has to look at viruses. In other parts of the world,

there are many viruses that are tick transmitted and cause very nasty diseases.

And we do not have one in Australia? Well, I cannot believe that. I cannot

believe that, senators. There have to be some viral tick-transmitted infections

in Australia; it is just that we do not know what they are.[40]

2.41

Both patient advocacy groups and medical authorities highlighted that

more research is needed into a range of key areas including identifying

possible pathogens in ticks and other vectors and clinical studies of patients.

These opportunities for research are examined in detail in Chapter 4.

2.42

A number of submitters and witnesses highlighted the need for better

education and awareness about preventing tick bites to avoid any potential

illnesses. Professor Peter Collignon told the committee:

We should avoid people being bitten by ticks. Ticks are bad

for lots of reasons, the same as mosquitos are really bad for people with, in

Australia, Ross River virus, Barmah Forest virus and a lot of things. So the

two insects that I think we should avoid being bitten by are ticks and

mosquitoes. I think we need to have a program to say what to do and,

particularly, how you remove a tick without causing more damage by squirting

more toxins or whatever into the person. So, yes, I think we need a tick

education program.[41]

2.43

The department noted in its submission that it is committed to education

and awareness raising about the prevention of tick bites and has produced a

publicly available information sheet on tick bites:[42]

In an effort to prevent tick-borne bites [sic] and raise

awareness of tick bite first aid, we collaborated with the National Arbovirus

and Malaria Advisory Committee as well as with states and territories on a tick

bite prevention document for public distribution. It is hoped in future we will

incorporate emerging research into tick bite associated mammalian meat allergy

and newer techniques for tick removal. The department is committed to such

education and awareness raising.[43]

Committee

view

2.44

The committee acknowledges that there is a debate about whether or not

Lyme disease is endemic to Australia. The committee notes the position of the

Chief Medical Officer that Lyme disease is not endemic to Australia as the

species of Borrelia bacteria responsible for causing the disease have

not been identified in Australia. The committee also notes evidence from Dr

Gary Lum that acknowledges that there may be another causative agent or agents

for the chronic debilitating illness described by patients.

2.45

The committee acknowledges that there may be illnesses transmitted by

ticks and potentially other vectors that warrant further research. The

committee notes that this issue needs further inquiry.

2.46

The committee recognises that more could be done to educate the public

and medical professionals about the risk of tick bites and tick-related

illnesses in Australia, as well as classical Lyme disease acquired overseas.

Treatment for patients diagnosed with Lyme-like illness

2.47

Patient advocacy groups argue that because Lyme disease is not

recognised as being endemic to Australia, patients seeking treatment experience

significant challenges accessing treatment.[44]

These difficulties include:

-

denial that someone is ill and denial of care;

-

stigma and humiliation associated with Lyme-like illness from some

medical services;

-

accessibility and costs of treatments prescribed by 'Lyme

literate practitioners'; and

-

limitations placed on 'Lyme literate' practitioners by medical

authorities.

Stigma and Lyme-like illness

2.48

Submitters expressed concern that because Lyme-like illness is not

recognised in Australia, patients experience significant stigma when seeking

treatment from some medical practitioners. These submitters note that medical

practitioners dismiss Lyme disease as a possible diagnosis, arguing that

Australia is not an endemic area and therefore Lyme disease does not exist

here.[45]

2.49

The committee notes that a large proportion of submitters to the inquiry

requested to have their submissions marked as either name withheld or

confidential to avoid any possible negative repercussions from their family,

friends, employers and medical practitioners.

2.50

One submitter described the treatment her 29 year old daughter had

received from medical professionals when she presented with Lyme-like illness:

The worst part of having this illness is the treatment and

discrimination that she has received by the majority of the medical profession.

She always had to justify why she was there and try to get them to understand

that she has pain, but after [a] brief discussion she would be told that there

is nothing medically wrong with her and her illness doesn't exist and that

stress is causing it all.[46]

2.51

Similarly, Ms Emily O'Sullivan, writing on behalf of her sister Amy, who

has been suffering chronic debilitating symptoms for 10 years and has been

diagnosed with Lyme-like illness, submitted that:

The Australian medical community not only fails to recognise

the disease but seem to have a proactive aversion to accepting Lyme Disease as

a possible diagnosis. This has left Amy in an unnerving cycle of denied care.

If she claimed to have Lyme Disease in GP clinics and ... hospitals (even with positive

blood tests), she was deemed 'crazy or looking for drugs' and didn’t receive

care because 'Lyme Disease doesn't exist in Australia'.[47]

2.52

The committee heard from a number of organisations representing patients

that indicated that patients are not treated with respect and care by some

medical practitioners. The LDAA noted in its submission that it receives:

... constant updates from Australians about how terribly they

are treated by the medical profession if they mention that they suspect or have

Lyme disease. Patient's [sic] routinely report poor treatment by Australian

GPs, infectious disease specialists and other hospital and specialist staff.[48]

2.53

The LDAA notes that the name 'Lyme disease' has attracted such a stigma

that 'many patients routinely advise others not to mention the disease at all

when reporting their medical history'.[49]

2.54

The committee is particularly concerned by evidence that suggests some

patients are humiliated or insulted by medical practitioners for seeking tests

or treatments for Lyme-like illness.[50]

The Australian Chronic Infectious and Inflammatory Disease Society (ACIIDS),

representing 'Lyme literate' practitioners, indicated that many patients have been

traumatised by some medical practitioners:

Discrimination against patients suffering from this illness,

and the doctors who treat them, is rife. Many patients have been traumatised by

their experience with medical specialists and in hospital emergency

departments; they have been subject to derision and verbal abuse.[51]

2.55

For example, one submitter described how their neurologist ridiculed

them when they brought up Lyme disease:

[My neurologist] spent a whole appointment ridiculing me and

asking me why I 'thought I had Lyme'. Repeating 'Lyme Disease is not in

Australia' [and] 'It can’t be Lyme Disease, we don't have Lyme in Australia'

[and] 'Show me proof it's here'[.]

I mentioned the paper that had just been realised [sic] from

Curtain [sic] University. This was found to have Borrelia on our native Fauna.

'That's on animals' he says.

So I leave another appointment in tears, frustrated and going

nowhere.[52]

2.56

One submitter, the father of a child with Lyme-like illness, said that

over three years of seeking treatment for his daughter the family faced a

series of refusals to treat and abuse by medical practitioners. During an

appointment with one neurologist, the family was subjected to a 'highly

abusive, emotional and irrational' outburst that included accusing the child of

feigning the symptoms and 'personal insults and attacks on the character' of

the child and their parents that 'deeply traumatised' the family.[53]

2.57

'Lyme literate' practitioners, such as Dr Richard Schloeffel, suggest

that the treatment of patients with Lyme-like illness by some medical

practitioners amounts to malpractice:

I cannot talk for other doctors and their thought processes,

but I would like to say to every doctor in Australia, 'Wake up to yourselves.

Start listening that we've got a real illness. Let's have a proper

conversation. Let's do the proper science. Let's fund it ... But we have to put

money into it, we have to have a proper conversation and the denialism has to

stop, because that is actually malpractice. It is actually negligence on the

part of the medical profession.[54]

2.58

Some medical authorities do not accept that there is any particular

stigma associated with Lyme disease or Lyme-like illness. For example, the

Australian Rickettsial Reference Laboratory submitted:

We do not accept that there is any more stigma associated

with "Lyme-like illness" than there is to many other medical

conditions from which many Australian patients already also suffer. Stigma,

where it exists, can be broken down by community education over time.

"Stigma" may be in the mind of the beholder. Some

patients may perceive that they are being stigmatised, but are probably not.

Their doctor is simply trying to obtain a diagnosis of their condition and

trying to treat the patient with the best of intentions and based on the

current state of medical knowledge. There are many patients who have an illness

that has not been currently diagnosed and for which there may be no recognised

treatment. Patients with "Lyme-like illness" are not the only

patients in this unfortunate position.[55]

2.59

Medical authorities noted that just because there is no evidence that

Lyme disease is endemic to Australia, it does not mean that doctors don't care

about the welfare of patients. Professor Samuel Zagarella told the committee:

When doctors say that Lyme disease does not exist in

Australia I think that a lot of people misinterpret that as being non-caring.

The question is whether these people are suffering from Lyme disease [or] a

different disease. We believe that at the moment there is no evidence to say

that they are suffering from Lyme disease caused by ticks, and caused by

Borrelia burgdorferi specifically. These people may be suffering from other

conditions. There are a lot of non-specific symptoms that these people suffer

from, such as arthritis, arthralgia, weakness, lethargy, pain and depression.

They certainly have some issues, but there is no evidence that Lyme disease as

such exists in Australia.[56]

Measures to reduce stigma

2.60

Some witnesses suggested that the stigma experienced by patients could

be reduced by avoiding use of the names 'Lyme disease' or 'Lyme-like illness'.

As noted in Chapter 1, submitters reported that they do not care what their

illness is called; they just want to be able to access treatment.

2.61

One alternative name suggested by Dr Lance Sanders is Hunter Valley

disease (HVD), in reference to the first documented case of a Lyme-like illness

reported in the Hunter Valley in the 1980s. Dr Sanders noted that this broad

term does not assume that the cause or causes for the symptoms have been

identified.[57]

2.62

In the United Kingdom, the name 'chronic arthropod-borne neuropathy' is

suggested by Dr Matthew Dryden to describe the range of symptoms experienced by

patients similar to those in Australia.[58]

2.63

Other possible names for the condition are advocated for by 'Lyme

literate' practitioners who argue that the symptoms are caused by Borreliosis

and a range of co-infections, such as US physician Dr Richard Horowitz.[59]

The name Multiple Systemic Infectious Disease Syndrome (MSIDS) is already used

by some patient advocacy groups in Western Australia in an attempt to move away

from the association with Lyme disease.[60]

2.64

Dr Lum told the committee that the department would support moving away

from the 'Lyme' label to better describe the 'chronic debilitating illness that

manifests as a constellation of chronic debilitating symptoms' described by

submitters:

We are well aware from the patient community and from various

members of the medical profession that moving right away from the notion of

Lyme disease and Lyme-disease-like illness is probably a very good move.

The problem that we have in Australia in terms of how we work

with patients, advocacy groups and the medical profession is that this is not

unique to Australia. The issue of a chronic Lyme disease is very contentious

and very controversial to the extent that we would like to steer away from

that. That is why in the work that we have been doing we have tried to

distinguish it by describing a chronic debilitating illness that manifests as a

constellation of chronic debilitating symptoms. That is a mouthful and I would

not propose that as a name. What I am trying to suggest though is that getting

away from that name is probably a very good move.[61]

2.65

Another measure to reduce stigma recommended by patients and advocacy

groups is formal recognition by Australian medical authorities of Lyme-like

illness.[62]

At its Brisbane hearing, the committee was presented with a 'Time to Recognise

Lyme' clock by Ms Karen Smith and Mr Matt Chant.[63]

Mr Chant told the committee:

The time to recognise Lyme clock is a call to action to show

that acknowledgement and treatment can help restore hope and health, that the

denial of Lyme and other vector borne diseases in Australia is causing

devastation and the loss of years of people's lives, and, in far too many

instances, their death.[64]

2.66

However, as noted in Chapter 1, Australian medical authorities do

not recognise Lyme-like illness as a defined condition, noting that it may be

used to describe a 'constellation of debilitating symptoms'.[65]

Committee

view

2.67

The committee is concerned by the treatment of patients diagnosed with

Lyme-like illness by some medical practitioners.

2.68

The committee notes that there are issues that need further inquiry,

such as:

-

ways to improve education and awareness about Lyme disease

acquired overseas;

-

ways to improve Australia's health care system to better meet the

needs of Australians with chronic illness; and

-

possible pathways for identifying an appropriate name and

definition for Lyme-like illness.

Accessibility and cost of treatment

2.69

A large number of patients diagnosed with Lyme-like illness expressed

concerns about the accessibility and high cost of treatments prescribed by

'Lyme literate' practitioners. 'Lyme literate' practitioners often prescribe a

course of treatment that may include antibiotics and other natural remedies

that are not supported by Medicare or the pharmaceutical benefits scheme (PBS).[66]

2.70

The committee heard that the cost of consulting 'Lyme literate'

practitioners is very expensive, with practitioners allegedly charging between

$300 and $900 for consultations.[67]

Diagnostic tests used by 'Lyme literate' practitioners also involve significant

expense (for example, $800 for tests in Australia and $2 000 for tests from

overseas laboratories).[68]

2.71

The treatments prescribed by 'Lyme literate' practitioners are also very

expensive, often costing hundreds of dollars per week. In one case, a submitter

claims to have spent over $100,000 on treatment since diagnosis.[69]

As a result of the high costs, a number of submitters, particularly those

receiving welfare or pension payments, note that they have not been able to

afford the prescribed treatments.[70]

For example, one submitter noted:

One drug for one of the coinfections alone costs over $1000

per month (and commonly needs to be taken for several months) but $6.10 if on

the PBS. This is just one example and most prescription treatments needed for

Lyme and coinfections are unsubsidized on the PBS so it is obvious that it

quickly becomes extremely costly to try to gain effective treatment for this

illness. The financial burden is enormous and I don't know what I'll do when I

run out of money.[71]

2.72

In some cases, submitters highlighted that some treatments prescribed by

'Lyme literate' doctors are not available in Australia. For example, submitters

have been referred to a clinic in Germany (Klinik St Georg in Bad Aibling) to

undertake 'hyperthermia treatment', where the body is heated to kill off

bacteria. This treatment is not available in Australia and costs approximately

$30 000 per course.[72]

Other submitters were referred to other similarly expensive treatments in the

US or elsewhere overseas (such as ozone therapy in Indonesia).[73]

2.73

As a result of these high costs, a number of submitters have highlighted

that they were experiencing significant financial hardship. Many submitters

reported having sold or mortgaged their homes, borrowed money from family and

friends or moved in with their parents or carers in order to afford treatments.[74]

2.74

Submitters have also highlighted that because Lyme-like illness is not formally

recognised, they have experienced difficulties in accessing social welfare

payments, income protection insurance and/or early access to superannuation to

pay for treatment and expressed concern and frustration that they did not

qualify for these payments and services.[75]

2.75

The department noted that to address the costs of treatments prescribed

by 'Lyme literate' practitioners, it would welcome an application for a review

of treatments to determine whether they could be included in the PBS:

...given the desire by patients and advocates for subsidised

pharmaceutical agents, the department would welcome a submission by the

advocacy groups to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee for a review

of the evidence.[76]

Appropriateness of treatments

2.76

The committee also heard concerns from medical authorities about some of

the treatments offered by 'Lyme literate' practitioners, such as side-effects

from antibiotics, infections from intravenous catheters (such as PICC lines)

and potential toxins from unregulated medications.[77]

These authorities argue that these treatments are not evidence based and risk

causing harm to patients.[78]

2.77

For example, one infectious disease specialist submitted:

I have been referred patients with Lyme disease, or such

patients have been referred to my colleagues. Sometime they already have

another diagnosis such as Motor Neurone Disease (MND). Then they are offered a

different diagnosis in a non-accredited lab, usually overseas. The lab is

usually not accredited in the overseas country and charges much more for tests

than mainstream labs ...

The patients are often given multiple diagnoses, none of

which are seen in Australia such as Babesiosis. In addition the treatment is

not standard, even were the diagnosis to be correct and invariably is for much

longer than in the IDSA (Infectious Diseases Society of America) guidelines. In

other words, even were the diagnosis to be correct the treatment is not

standard, and almost always has greater risks of side effects than conventional

treatment ...

The circumstances are not universal but there is a cluster of

patients diagnosed outside of medicine in un accredited [sic] laboratories and

given unorthodox treatment to the potentially severe detriment of their medical

and physical health as well as bearing a great financial and psychological

burden.[79]

2.78

In particular, the committee heard concerns about the use of long-term

antibiotics to address symptoms ascribed to Lyme-like illness. The Communicable

Diseases Network Australia, supported by state and territory health

departments, noted that:

There is no evidence to support the use of combination

antibiotics, immunoglobulin, hyperbaric oxygen, specific nutritional

supplements, or prolonged courses of antibiotics for the management of Lyme

disease.[80]

2.79

Associate Professor Samuel Zagarella from the Australasian College of

Dermatologists provided the committee with a recent study of a randomised trial

of long-term antibiotic therapy for symptoms attributed to Lyme disease in

Europe which concluded:

In patients with persistent symptoms attributed to Lyme

disease, longer-term antibiotic treatment did not have additional beneficial

effects on health-related quality of life beyond those with shorter-term

treatment.[81]

2.80

The RCPA further noted that the consequences of long-term antibiotic use

can have negative effects for both the individual and the broader community:

Unproven long term broad spectrum antibiotic treatment is not

only potentially harmful to the individual patient due to side-effects up to

and including death, it is harmful to the patient and the Australian community

in general because it promotes the proliferation of multi-drug resistant

organisms. This resistance renders all anti-biotics ineffective against common

(non-Lyme Disease) infections and is a genuine crisis in modern healthcare.[82]

2.81

However, 'Lyme literate' practitioners told the committee that the use

of long-term antibiotics was evidence based and in many cases assisted patients

to get better. Dr Richard Schloeffel, a Lyme literate practitioner in Sydney,

told the committee:

We have treated 4 000 patients in five years. We are

currently treating only 1 500 patients. Of the other 2 500 patients we have

treated, most are better. They are getting better because they are having an

appropriate diagnosis and appropriate treatment, sometimes with long-term

antibiotics—oral in the main. But because we have so many sick patients we are

doing a lot of intravenous therapies as well, including intravenous antibiotics

for long periods of time, which is leading to a positive outcome, but under the

same rigor that any intensive therapy would require, and we are doctors who are

extremely qualified to do this work.[83]

Committee

view

2.82

The committee notes that the following issues need further inquiry:

-

treatments prescribed for patients with Lyme-like illness,

including costs, efficacy and evidence base; and

-

the potential for a review of treatments by an expert panel.

Limitations on 'Lyme literate'

practitioners

2.83

Submitters expressed particular concern that 'Lyme literate'

practitioners experience stigma from medical authorities. In some cases,

practitioners have ceased providing treatment due to sanctions by or fear of

sanctions by medical authorities such as the Australian Health Practitioner

Regulation Agency (AHPRA). These submitters argue strongly that 'Lyme literate'

practitioners should not be prohibited from treating for Lyme-like illness.[84]

2.84

The committee notes that a number of practitioners who made submissions

to the inquiry requested that their name be withheld due to fear of

disciplinary action by AHPRA.[85]

Mr John Curnow, whose wife suffered from Lyme-like illness, noted in his

submission: 'The few doctors that do try to treat [this] Lyme like illness are

ostracised and called charlatans by their colleagues'.[86]

2.85

The LDAA also addressed this issue, noting that:

Of serious concern is the increasing level of complaints

being directed at doctors who are treating patients with Lyme disease. Over the

past three years there have been conditions placed on three doctors (Ladhams,

Du Preez and Kemp) treating patients with Lyme disease by the Australian Health

Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). The conditions are specific in response

to Lyme disease and relate to the diagnosis, treatment and prescribing

practices of the doctors concerned.[87]

2.86

According to the LDAA:

The small handful of doctors who are treating patients in

Australia are being bullied and badgered from within their profession and also

by AHPRA. It's probable that any Australian doctor that chooses to treat

Lyme-like disease will be investigated, given that they administer antibiotics

for a longer period of time than the one month treatment protocol and operate

outside the ATG's [Australian Therapeutic Guidelines].[88]

2.87

One doctor who made a submission to this inquiry noted that the effect

of such investigations was to constrain those doctors in their ability to treat

patients:

To my knowledge there are 7 medical practitioners who have

been 'targeted' for investigation and / or disciplinary measures. This makes

those of us willing to treat this condition fearful of such treatment.[89]

2.88

As a result of limitations placed on their practitioners by AHPRA, some

submitters noted that they were no longer able to get treatment. For example,

one submitter noted:

In 2013 I came under the care of a Lyme-literate doctor and

began receiving antibiotic treatment via a Portacath. I started to notice

changes quickly and then improvements within months...

In late 2013 my Lyme literate doctor faced disciplinary

action and was [told] he could no longer treat patients with Lyme disease. This

left me without a Lyme-literate doctor, or any doctor at all and with no access

to assistance with my Portacath for IV treatment. My husband rang many medical

centres in our local Redlands area and no one would help me.

As a result my health rapidly declined and I was dealing with

a Portacath that clotted and had no medical practitioner to assist with

flushing it. Thankfully my husband learned how to manage my Portacath with

videos that he found on YouTube.[90]

2.89

In response to this perception, representatives from AHPRA and the

Medical Board of Australia (MBA) told the committee at its Brisbane hearing that

AHPRA does not target Lyme-literate practitioners and only responds on the

basis of complaints:

... we recognise that there is a perception by some patients

that we have targeted medical practitioners who diagnose, treat or have a

relationship with Lyme-like illness. I would like to put it quite clearly on

the record that this is not true. In all the Lyme-related cases that we are or

have been involved with, the board has always acted—not in isolation or on its

own behalf—in response to a complaint.[91]

2.90

The Australian Medical Association (AMA) submitted that investigations

are initiated on the basis of specific complaints about the individual

practitioner:

The very small number of doctors who come before the MBA

often have a history of complaints made about them from the public and the

profession. The conditions imposed on the registration of any individual

medical practitioner are always specific to that practitioner. They do not

reflect the Board's view about any disease state or treatment regime. The AMA

continues to support the role of AHPRA and the MBA in this respect.[92]

2.91

Representatives from AHPRA and the MBA further stressed that in most

cases regarding Lyme literate practitioners, they have decided not to act. In

the small minority of cases where AHPRA does act, this is in response to the

professional conduct of the practitioners in question:

I would like to point out that in the majority of

notifications that have been in some way related with Lyme disease or Lyme in

some way, the board has decided not to act—not to act, to protect the public.

The matters have simply been investigated and then closed. It is in the small

number of cases where there is a greater risk, we perceive, to the public that

the board has taken a regulatory action to protect the public. It is on the public

record that we have received notifications about practitioners who have

diagnosed and treated Lyme disease. I would like to point out that it is not

because of the diagnosis that they are there before us, but because of their

professional conduct in the management of these patients. It is for these

patients that we have taken regulatory action.[93]

2.92

The MBA and AHPRA told the committee that in 2013-14 and 2014-15, of

complaints received relating to the treatment of Lyme-like symptoms:

-

9.3 per cent were made by medical practitioners (as mandatory

notifications under the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law); and

-

90.7 per cent were made by members of the public.[94]

2.93

The MBA and AHPRA listed some of the concerns related to Lyme disease or

Lyme-like illness which have led to an investigation of a medical practitioner:

-

the use of unconventional

diagnostic techniques (e.g. kinesiology) to diagnose Lyme-like disease;

-

the reliance on non-accredited

laboratories to diagnose Lyme-like disease;

-

the potential for financial

exploitation of patients, both through the use of overseas non-accredited

laboratories and in charging high fees for services;

-

not referring patients with

complex diagnoses to specialists, where this would have been appropriate;

-

not managing other co-existing

medical conditions once Lyme-like disease was diagnosed;

-

diagnosis of a large proportion of

a medical practitioner's patients with Lyme-like disease without considering or

excluding other conditions. There is a concern that patients may be deprived of

the opportunity to have more appropriate treatment for another condition

because the alternative condition is not considered once Lyme-like illness has

been diagnosed. Treating Lyme-like illness with long-term antibiotic treatment,

in the absence of an identified infection, is of concern. This management is at

odds with advice from public health authorities regarding the dangers of

antibiotic resistance. We understand that some practitioners are prescribing

and administering antibiotics for years (whereas the treatment of Lyme disease

is for weeks); and

-

treatment for Lyme-like disease

resulting in complications and interacting or interfering with other

treatments. Examples include, use of large lines (e.g. PICC lines) to

administer long-term antibiotics, which can result in infections and

thrombosis, and antibiotics interacting with other necessary treatments.[95]

2.94

The committee heard that AHPRA and the MBA have not considered ways to

communicate decisions about 'Lyme literate' practitioners to other practitioners

and the patient community. At the suggestion of the committee that this be

considered, Associate Professor Stephen Bradshaw from AHPRA told the committee:

To be honest with you, we have not considered what you have

just suggested. We may consider that after. I re-emphasise to you that we are

not a disease-focused organisation—be it Lyme disease, cancer or whatever. We

are looking for good medical practice. It is disappointing that there is this

perception out there that we are targeting particular groups; I re-emphasise

and will keep re-emphasising that we certainly are not. At the end of the day,

the number of practitioners that have regulatory action taken against them on

this topic is extremely small. There are huge other areas of practice that have

a lot more practitioners before us than practitioners looking after patients

with Lyme disease.[96]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page